Monday January 13, 1896

DEGREES FOR WOMEN AT CAMBRIDGE: ADMISSION OF WOMEN TO DEGREES IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE.

We, the undersigned Members of the Senate, are of the opinion that the time has arrived for re-opening the question of admitting women to Degrees in the University of Cambridge. We therefore respectfully beg that the Council of the Senate will nominate a Syndicate to consider on what conditions and with what restrictions, if any, women should be admitted to degrees in the University.

Nearly 400 members of the Senate have, we understand, nearly affixed their signatures.

SATURDAY MARCH 14, 1896

ALIEN IMMIGRATION IN EAST LONDON.

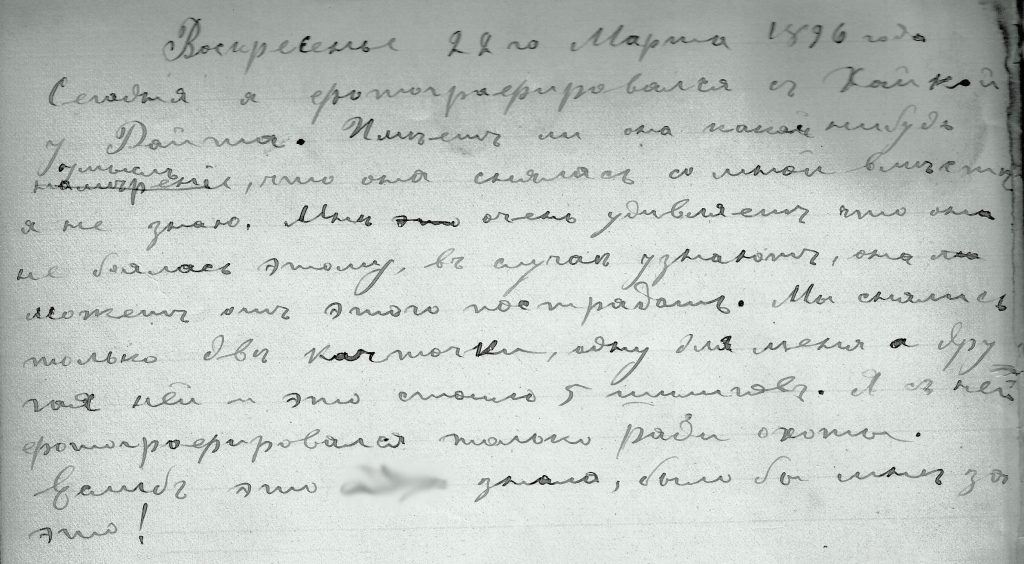

Abraham’s Diary, London

Written in Russian

22nd March 1896

5th April 1896

Today I had my picture taken with Dora in Dight’s studio. We bought half a dozen cabinet pictures for 10 shillings. Today I’ve also started to ‘thee and thou’ her. Gradually I’m getting more and more involved with her.

12th April 1896

15th April 1896

I had a row with a foreman today. He came to check my work and found an area where my sandpapering wasn’t good enough. He asked me whether I’d been too drunk to notice the defect. I answered that I had noticed it but didn’t want to put it right because the job was very badly paid, whereas if I’d have been given a better job I would have done it better. He screamed at the top of his voice that he wouldn’t stand me telling him what jobs to give me and that he wouldn’t give me better jobs anyway. I didn’t let him shout for long, but told him to “keep his bleeding noise”. He got terribly offended and shut up. Then he hastily passed my job and left. Will this incident lead to my being sacked? Tomorrow I have to finish off the second part of the job and get another order.

16th April 1896

Today at 10 o’clock I finished the job. The junior foreman passed it and then told me to pack my tools and go. I decided not to leave as a fool, thinking that I might be able to give him a thrashing before I went, or at least give him an earful. I went downstairs to the office, but the junior foreman ran ahead of me, stood in the doorway and wouldn’t let me in. The foreman asked me what I wanted. I told him I wanted an order. “I won’t give you an order”, he said. “Why?” “For no reason.” I wanted to enter the office but the junior foreman locked the door. “I shall find you”, I yelled. At this moment he jumped out and screamed: “Do you want to kill me?” I argued with him, pointing out the loathsome way in which he treated his workers. In the end I packed my tools and left.

When I came downstairs I was detained and told to wait for the ‘gov’ner and a policeman, who’d already been sent for. When both had arrived, the latter took down my particulars. The gov’ner tore me off a strip and gave me a sermon as to my future behaviour. “It’s no good” he said, “to rebel in this manner. I’m not obliged to employ you, any more than you’re obliged to work for me. If you’d left quietly, I might have employed you again, had you come asking for work after a while”. I replied that I had no intention of asking him for work again, that I wasn’t sorry to go, that I was sorry for one thing only: that a brute such as he was able to keep me, or throw me out like a useless rag, as he pleased. With this I left. Once again I have neither job nor money. All the money I’ve got amounts to 30 shillings 1. One week without work and I’ll be left penniless as they say. This is the result of two years’ work!

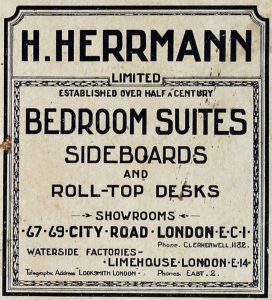

17th April 1896, London

I went to Hermann’s factory asking for a job and was told to bring my tools, but for some reason I can’t make myself take up my tools and go. The tool box is standing right here in front of me. Three times I got up to go, three times I stood near the box, unable to brave it and go to the factory. But, really, what will come of it? I shall continue to live in a state of perpetual fear. If I get the sack from this factory too, my situation will be the same as now, or even worse. By that time I might already be engaged to Dora, or even married to her. My mother and my sister with her children might be here by that time, then my state of affairs will be ten times worse, if I don’t get used to manual work. Shall I go back to private masters, where manual work is done? Shivers run down my spine when I remember the filth, the stench, the charcoal fumes, the lack of space—this is what you have to put up with to get work. I don’t feel strong enough to work in such conditions. Maybe if I went to another town, I’d find it easier to work. I’d very much like to go to Manchester and I think I’d benefit from it in two ways. Firstly, I wouldn’t have so many acquaintances to spend time with, therefore it would be easier to get used to the way of life. Working late, or on Sundays, wouldn’t be such a big deal, for I wouldn’t have anywhere to go anyway. Secondly, I should get out of a rather difficult situation. I’ve written to my mother that if she agrees to come without my sister, with only one child, I’ll send her the money for the journey. I don’t know where on earth I shall get this money from. I thought I’d be able to save some by Whitsun and borrow the rest. I might not be able to do it now, so if I leave I’ll be able to draw the time out a little, although I’d be very sorry to have to do it. It will hurt them a lot when they hear about it. I promised Dora a ring at Whitsun, too, and once again I haven’t got a clue how to get it. I promised only because I couldn’t bear her family and friends nagging her that I wasn’t giving her a ring and was therefore certainly deceiving her. If I leave, everything will change, for better or for worse. I feel very sorry for Dora: now she will really suffer from friendly tongues, telling her that I was deceiving her all along and have now abandoned her. I have no intention of abandoning her, and if I do go, I shall leave all my belongings with her. I feel a great love for her now.

I went to Hermann’s factory asking for a job and was told to bring my tools, but for some reason I can’t make myself take up my tools and go. The tool box is standing right here in front of me. Three times I got up to go, three times I stood near the box, unable to brave it and go to the factory. But, really, what will come of it? I shall continue to live in a state of perpetual fear. If I get the sack from this factory too, my situation will be the same as now, or even worse. By that time I might already be engaged to Dora, or even married to her. My mother and my sister with her children might be here by that time, then my state of affairs will be ten times worse, if I don’t get used to manual work. Shall I go back to private masters, where manual work is done? Shivers run down my spine when I remember the filth, the stench, the charcoal fumes, the lack of space—this is what you have to put up with to get work. I don’t feel strong enough to work in such conditions. Maybe if I went to another town, I’d find it easier to work. I’d very much like to go to Manchester and I think I’d benefit from it in two ways. Firstly, I wouldn’t have so many acquaintances to spend time with, therefore it would be easier to get used to the way of life. Working late, or on Sundays, wouldn’t be such a big deal, for I wouldn’t have anywhere to go anyway. Secondly, I should get out of a rather difficult situation. I’ve written to my mother that if she agrees to come without my sister, with only one child, I’ll send her the money for the journey. I don’t know where on earth I shall get this money from. I thought I’d be able to save some by Whitsun and borrow the rest. I might not be able to do it now, so if I leave I’ll be able to draw the time out a little, although I’d be very sorry to have to do it. It will hurt them a lot when they hear about it. I promised Dora a ring at Whitsun, too, and once again I haven’t got a clue how to get it. I promised only because I couldn’t bear her family and friends nagging her that I wasn’t giving her a ring and was therefore certainly deceiving her. If I leave, everything will change, for better or for worse. I feel very sorry for Dora: now she will really suffer from friendly tongues, telling her that I was deceiving her all along and have now abandoned her. I have no intention of abandoning her, and if I do go, I shall leave all my belongings with her. I feel a great love for her now.

20th April 1896, London

Today I started working for Bloomberg at 25 Charlot Street as a piece-worker. I began making two chests. There is a worker there with whom I used to work at Lebus 2. He promised to show me how to do it.

25th April 1896, London

30th April 1896, London

31st December 1896, 11.45 p.m., London

In half an hour’s time another year of my life will fall into oblivion. I did not get anything special out of it, so I am not going to feel sorry that it is gone. It broke all my dreams and destroyed my aspirations and wishes. At the beginning of the year I tried to keep my promise towards my mother and sister and accompany them to London, but I still can’t do it… But…

I can hear the bells of Spitalfields church and some other roar – a mixture of sounds of horns and whistles. I do not know where it is coming from. They are announcing a New Year. I am seeing it in a tiny room at 39 Booth St. It is so dark, dirty and boring here! I suppose it is still the life of the passing year. So go away! Go away as quickly as possible! You have been such a dark and boring year! And even if it is going to bring my death nearer, I prefer dying to being embraced by you! It was more than once that you left me hungry in June and August. It was more than once that you were torturing me by not giving me a chance to see my parents or even send them some money. You punished me so often by not letting me show my darling Dora my real self.

You might say that you are not to blame and that I simply do not know how to make the most of you. But if I had known how to make the most of it you would not have punished me so severely. Maybe you can point at some other people who did know how to use their time properly and got what they wanted! But still… tell me “Have I been so useless?” During the whole year I worked so hard! I did not miss a single day. Even when you let me stay off work I still worked as hard as I could. So that is how you have rewarded me for my efforts! You have given me nothing except three pawn tickets from a pawnshop for my two suits and my violin. You might say that I have wasted the money. But on what? On food? And how can I not eat? My food has always been so scarce and sometimes even disgusting, because I am saving as much as I can.

During the whole year I was never drunk and never played cards. I did not even allow myself to spend money on Dora apart from going to the park with her from time to time or to my sister’s. But it was nothing compared to what I should have spent on buying rings or some other presents for her. But you did not allow me to do that. You might say that I spent money on books or that I sent some of it to my mother. Even if I did, it was not a lot. It was not a sufficient reward for a whole year’s work! How much did I spend on books? 15 shillings at the most—and that is for the whole year. I decided to have my Shakespeare bound. I had enough money for only one volume. The other two have been there for almost two months and I cannot get them. To say nothing about sending money to my mother. My poor mother! During the whole year I managed to send her only 20 roubles. And not all of this money was mine. You have been so cruel to me! So I am pleased that you are going away. The sooner—the better. But to whom am I talking? It has been already two hours since you dropped down into an abyss. And for two hours the New Year has been looking into my window. It is examining my room, like a new architect examines the work left after an old deceased architect. I wish the New Year did not follow the same pattern, especially now that I have told him the whole story (I think I should paint the pattern with other, brighter colours. He will be confused and might follow the lighter ones.) Last year was for me … (I honestly cannot find anything positive that I could boast about. …oh, yes, I do remember, although it did not belong to the last year, but the New Year would not know).

Клиника “Эмпатия” предлагает профессиональную поддержку в области ментального благополучия.

Здесь принимают квалифицированные психологи и психотерапевты, готовые помочь в сложных ситуациях.

В “Эмпатии” используют современные методики терапии и персональные программы.

Центр поддерживает при стрессах, панических атаках и других проблемах.

Если вы нуждаетесь в безопасное место для решения психологических проблем, “Эмпатия” — отличный выбор.

wiki.lintense.com

Процесс сертификации товаров является важным этапом для подтверждения соответствия стандартам. Прохождение сертификации позволяет укрепить доверие потребителей. Продукция, прошедшая сертификацию легче находит своих покупателей. К тому же, сертификация снижает риски. Следует учитывать, что разные отрасли требуют различных видов сертификации.

добровольная сертификация

В условиях большого города доставка еды стала неотъемлемой частью повседневной жизни. Множество людей ценят удобство, которое она предоставляет, позволяя освободить время. Сейчас доставка еды — это не только способ быстро перекусить, но и важная часть в жизни busy людей. Рынок доставки предлагают разнообразие блюд, что делает этот сервис особенно актуальным для людей, ценящих комфорт и вкус. Без мгновенной доставки сложно представить жизнь в мегаполисе, где каждый день приносит новые задачи и вызовы.

http://forum.drustvogil-galad.si/index.php/topic,121964.new.html#new

The digital drugstore features a broad selection of health products with competitive pricing.

Customers can discover both prescription and over-the-counter medicines suitable for different health conditions.

We strive to maintain safe and effective medications without breaking the bank.

Quick and dependable delivery provides that your order arrives on time.

Enjoy the ease of getting your meds on our platform.

https://www.apsense.com/article/838620-cialis-black-800-mg-for-sale-finding-the-best-deals.html

В России сертификация имеет большое значение для подтверждения соответствия продукции установленным стандартам. Прохождение сертификации нужно как для бизнеса, так и для конечных пользователей. Документ о сертификации гарантирует соответствие товара нормам и требованиям. Особенно это актуально в таких отраслях, как пищевая промышленность, строительство и медицина. Сертификация помогает повысить доверие к бренду. Кроме того, сертификация может быть необходима для участия в тендерах и заключении договоров. В итоге, соблюдение сертификационных требований обеспечивает стабильность и успех компании.

сертификация качества продукции

I am glad to be one of several visitors on this outstanding website (:, thankyou for posting.

В России сертификация имеет большое значение в обеспечении качества и безопасности товаров и услуг. Она необходима как для производителей, так и для потребителей. Наличие сертификата подтверждает, что продукция прошла все необходимые проверки. Это особенно важно в таких отраслях, как пищевая промышленность, строительство и медицина. Прошедшие сертификацию компании чаще выбираются потребителями. Также сертификация может быть необходима для участия в тендерах и заключении договоров. Таким образом, соблюдение сертификационных требований обеспечивает стабильность и успех компании.

обязательная сертификация

На территории Российской Федерации сертификация играет важную роль для подтверждения соответствия продукции установленным стандартам. Прохождение сертификации нужно как для бизнеса, так и для конечных пользователей. Документ о сертификации гарантирует соответствие товара нормам и требованиям. Особенно это актуально в таких отраслях, как пищевая промышленность, строительство и медицина. Сертификация помогает повысить доверие к бренду. Кроме того, сертификация может быть необходима для участия в тендерах и заключении договоров. Таким образом, соблюдение сертификационных требований обеспечивает стабильность и успех компании.

сертификация качества

Stake Casino GameAthlon Casino is one of the leading crypto gambling as it was one of the pioneers.

Online gambling platforms is evolving and there are many options, but not all casinos provide the same quality of service.

This article, we will review the best casinos you can find in the Greek market and the benefits they offer who live in Greece.

Best online casinos of 2023 are shown in the table below. You will find the best casino websites as rated by our expert team.

For every casino, make sure to check the licensing, gaming software licenses, and security protocols to confirm security for all users on their websites.

If any of these elements are missing, or if we have difficulty finding them, we exclude that website from our list.

Casino software developers are another important factor in selecting an online casino. As a rule, if the previous factor is missing, you won’t find reliable providers like Microgaming represented on the site.

The best online casinos offer classic payment methods like Visa, and they should also offer digital payment services like Paysafecard and many others.

Vector Jet specializes in arranging private jet charters, collective flights, and cargo charters.

They offer customized solutions for private jet journeys, quick air transfers, rotorcraft services, and freight delivery, including time-critical and relief missions.

The company offers versatile travel options with individually tailored fleet suggestions, round-the-clock management, and help with special requests, such as flying with pets or hard-to-reach destination access.

Complementary services feature jet leasing, sales, and fleet oversight.

VectorJet serves as an liaison between customers and third-party operators, ensuring luxury, convenience, and efficiency.

Their mission is to make private aviation effortless, secure, and personally designed for every client.

vector-jet.com

Оказываем прокат автобусов и микроавтобусов с водителем корпоративным клиентам, малым и средним предприятиям, а также частным заказчикам.

Автобус для деловых поездок

Гарантируем комфортную и абсолютно безопасную перевозку для коллективов, организуя транспортные услуги на свадьбы, корпоративные встречи, экскурсии и разные мероприятия в городе Челябинске и Челябинской области.

Swiss watches have long been a gold standard in horology. Meticulously designed by legendary brands, they perfectly unite classic techniques with innovation.

Every component reflect superior attention to detail, from precision-engineered calibers to luxurious materials.

Owning a horological masterpiece is more than a way to check the hour. It signifies refined taste and exceptional durability.

No matter if you love a classic design, Swiss watches deliver remarkable precision that lasts for generations.

https://forum.mban.com.np/showthread.php?tid=7&pid=443#pid443

Luxury timepieces have long been a benchmark of excellence. Meticulously designed by legendary artisans, they perfectly unite tradition with innovation.

All elements reflect superior workmanship, from intricate mechanisms to high-end finishes.

Investing in a Swiss watch is not just about telling time. It signifies refined taste and uncompromising quality.

Whether you prefer a bold statement piece, Swiss watches deliver extraordinary reliability that lasts for generations.

http://maorma.otzforum.hostinguk.org/viewtopic.php?t=971

Darknet — это закрытая часть онлайн-пространства, куда можно попасть с использованием защищенные браузеры, например, через Tor.

Здесь доступны как законные, а также противозаконные платформы, например, форумы и прочие площадки.

Одной из известных торговых площадок считается Black Sprut, что занималась торговле разнообразной продукции, в частности противозаконные вещества.

https://bs2best

Эти площадки часто функционируют на анонимные платежи в целях анонимности операций.

Однако, власти время от времени блокируют основные незаконные платформы, но вскоре появляются другие площадки.

We offer a wide range of certified pharmaceutical products for different conditions.

Our platform guarantees quick and safe delivery to your location.

Each medication is supplied by licensed manufacturers so you get safety and quality.

Easily browse our catalog and place your order hassle-free.

If you have questions, Pharmacy experts is ready to assist you whenever you need.

Stay healthy with reliable medical store!

https://www.merchantcircle.com/blogs/imedix-new-york-ny/2024/10/Fildena-A-Popular-Choice-for-Improved-Circulation-and-Wellness/2834256

Прохождение сертификации в нашей стране по-прежнему считается ключевым процессом выхода продукции на рынок.

Процедура подтверждения качества подтверждает соответствие техническим регламентам и законам, что гарантирует защиту покупателей от небезопасной продукции.

сертификация качества

К тому же, сертификация помогает сотрудничество с партнерами и повышает конкурентные преимущества на рынке.

Без сертификации, не исключены юридические риски и барьеры при продаже товаров.

Вот почему, оформление документации не только требованием законодательства, и мощным инструментом устойчивого роста организации в России.

Сертификация на территории РФ остается важным процессом легальной реализации товаров.

Система сертификации гарантирует соответствие государственным стандартам и правилам, что, в свою очередь, защищает покупателей от фальсификата.

сертификация продукции

Также официальное подтверждение качества облегчает сотрудничество с заказчиками и открывает конкурентные преимущества на рынке.

Если продукция не сертифицирована, может возникнуть штрафы и барьеры в процессе реализации продукции.

Поэтому, оформление документации не просто формальностью, но и важным фактором устойчивого роста организации в России.

Даркнет — это анонимная зона сети, куда открывается доступ исключительно через специальные программы, например, через Tor.

Здесь доступны официальные , включая обменные сервисы и прочие площадки.

Одной из крупнейших торговых площадок была BlackSprut, которая специализировалась на торговле разных категорий.

bs2best at

Подобные площадки часто используют биткойны в целях анонимности транзакций.

Despite the popularity of modern wearable tech, mechanical watches remain everlasting.

A lot of enthusiasts value the artistry behind mechanical watches.

Compared to digital alternatives, which lose relevance, mechanical watches remain prestigious through generations.

http://www.anti-social.site/index.php?topic=1321.new#new

Prestigious watchmakers are always introducing exclusive mechanical models, showing that their desirability hasn’t faded.

For true enthusiasts, an automatic timepiece is not just an accessory, but a tribute to craftsmanship.

Though digital watches provide extra features, traditional timepieces carry history that stands the test of time.

Обзор BlackSprut: ключевые особенности

BlackSprut привлекает обсуждения многих пользователей. Но что это такое?

Эта площадка предлагает интересные функции для аудитории. Визуальная составляющая платформы характеризуется функциональностью, что делает его понятной даже для тех, кто впервые сталкивается с подобными сервисами.

Стоит учитывать, что этот ресурс работает по своим принципам, которые формируют его имидж на рынке.

Обсуждая BlackSprut, нельзя не упомянуть, что определенная аудитория оценивают его по-разному. Одни отмечают его удобство, другие же оценивают его более критично.

Подводя итоги, эта платформа продолжает быть темой дискуссий и вызывает заинтересованность разных слоев интернет-сообщества.

Обновленный домен БлэкСпрут – ищите здесь

Хотите найти актуальное зеркало на БлэкСпрут? Это можно сделать здесь.

bs2best at

Сайт может меняться, и лучше знать актуальный линк.

Свежий доступ всегда можно найти здесь.

Посмотрите рабочую ссылку прямо сейчас!

We offer a comprehensive collection of trusted medicines for various needs.

Our platform guarantees fast and reliable shipping to your location.

Each medication is sourced from certified suppliers for guaranteed safety and quality.

Easily browse our online store and make a purchase in minutes.

If you have questions, Customer service is ready to assist you whenever you need.

Prioritize your well-being with reliable e-pharmacy!

https://www.linkcentre.com/review/shailoo.gov.kg/ru/vybory-aprel-2021/environmental-health-impact-environment-public-health/

Наш сервис осуществляет помощью приезжих в СПб.

Мы помогаем в оформлении разрешений, временной регистрации, а также формальностях, связанных с трудоустройством.

Наши специалисты разъясняют по всем юридическим вопросам и дают советы оптимальные варианты.

Помогаем как с временным пребыванием, и в вопросах натурализации.

С нашей помощью, ваша адаптация пройдет легче, решить все юридические формальности и уверенно чувствовать себя в северной столице.

Свяжитесь с нами, чтобы узнать больше!

https://spb-migrant.ru/

Ordering medications online has become way more convenient than visiting a local drugstore.

There’s no reason to stand in queues or worry about limited availability.

E-pharmacies let you buy what you need from home.

Numerous websites have special deals compared to physical stores.

http://marshallplast.com/forum/index.php?topic=85.new#new

Additionally, it’s easy to browse different brands easily.

Reliable shipping means you get what you need fast.

Do you prefer purchasing drugs from the internet?

Обзор BlackSprut: ключевые особенности

BlackSprut удостаивается внимание широкой аудитории. Что делает его уникальным?

Данный ресурс предлагает разнообразные функции для аудитории. Интерфейс платформы выделяется функциональностью, что позволяет ей быть понятной даже для новичков.

Важно отметить, что этот ресурс обладает уникальными характеристиками, которые формируют его имидж в определенной среде.

При рассмотрении BlackSprut важно учитывать, что многие пользователи оценивают его по-разному. Многие подчеркивают его функциональность, а кто-то оценивают его более критично.

В целом, данный сервис остается объектом интереса и привлекает интерес разных пользователей.

Свежий домен БлэкСпрут – ищите здесь

Если нужен обновленный сайт BlackSprut, вы на верном пути.

bs2best

Сайт может меняться, и лучше знать обновленный домен.

Мы мониторим за изменениями и готовы поделиться актуальным линком.

Проверьте рабочую ссылку у нас!

This website provides access to a large variety of online slots, suitable for both beginners and experienced users.

On this site, you can discover classic slots, modern video slots, and progressive jackpots with high-quality visuals and immersive sound.

If you are into simple gameplay or seek complex features, this site has a perfect match.

https://1alimenty.ru/wp-content/pag/kakoe_postelynoe_belye_budet_horosho_smotretysya_v_komnate_podrostka.html

Every slot is playable anytime, no download needed, and perfectly tuned for both desktop and smartphone.

Besides slots, the site features slot guides, special offers, and user ratings to guide your play.

Register today, jump into the action, and have fun with the world of digital reels!

На нашем портале вам предоставляется возможность играть в большим выбором игровых слотов.

Эти слоты славятся живой визуализацией и захватывающим игровым процессом.

Каждый слот предлагает особые бонусные возможности, увеличивающие шансы на выигрыш.

1хбет зеркало рабочее

Игра в слоты подходит как новичков, так и опытных игроков.

Можно опробовать игру без ставки, после чего начать играть на реальные деньги.

Испытайте удачу и насладитесь неповторимой атмосферой игровых автоматов.

Demystifying health information is a crucial step towards better well-being. Many find medical jargon and research findings difficult to interpret. Investing time to learn basic health principles pays dividends. Understanding medical preparations, including their names and purposes, aids comprehension. It enables safer use of medications and adherence to treatments. Access to clear, understandable health content is therefore vital. The iMedix podcast focuses on making health topics accessible to everyone. As an online health information podcast, it’s incredibly convenient. Tune into the iMedix online Health Podcast for regular learning. iMedix.com is your gateway to their resources.

На нашем портале вам предоставляется возможность наслаждаться широким ассортиментом игровых слотов.

Эти слоты славятся красочной графикой и увлекательным игровым процессом.

Каждый игровой автомат предоставляет уникальные бонусные раунды, улучшающие шансы на успех.

1xbet

Слоты созданы для любителей азартных игр всех мастей.

Есть возможность воспользоваться демо-режимом, и потом испытать азарт игры на реальные ставки.

Попробуйте свои силы и окунитесь в захватывающий мир слотов.

Self-harm leading to death is a serious issue that impacts millions of people worldwide.

It is often connected to mental health issues, such as anxiety, stress, or addiction problems.

People who struggle with suicide may feel trapped and believe there’s no solution.

how-to-kill-yourself.com

We must spread knowledge about this subject and help vulnerable individuals.

Early support can reduce the risk, and finding help is a necessary first step.

If you or someone you know is struggling, please seek help.

You are not alone, and support exists.

На нашем портале вам предоставляется возможность играть в широким ассортиментом игровых автоматов.

Слоты обладают красочной графикой и интерактивным игровым процессом.

Каждый слот предлагает индивидуальные бонусные функции, улучшающие шансы на успех.

1xbet игровые автоматы

Игра в игровые автоматы предназначена как новичков, так и опытных игроков.

Вы можете играть бесплатно, после чего начать играть на реальные деньги.

Попробуйте свои силы и окунитесь в захватывающий мир слотов.

На этом сайте вы можете испытать широким ассортиментом игровых автоматов.

Эти слоты славятся живой визуализацией и захватывающим игровым процессом.

Каждый слот предлагает индивидуальные бонусные функции, улучшающие шансы на успех.

Mostbet

Игра в игровые автоматы предназначена любителей азартных игр всех мастей.

Можно опробовать игру без ставки, после чего начать играть на реальные деньги.

Испытайте удачу и насладитесь неповторимой атмосферой игровых автоматов.

Suicide is a serious issue that impacts many families worldwide.

It is often connected to psychological struggles, such as depression, trauma, or chemical dependency.

People who contemplate suicide may feel isolated and believe there’s no solution.

how-to-kill-yourself.com

Society needs to raise awareness about this matter and offer a helping hand.

Prevention can reduce the risk, and talking to someone is a necessary first step.

If you or someone you know is struggling, please seek help.

You are not alone, and support exists.

This website, you can discover lots of slot machines from leading developers.

Visitors can enjoy retro-style games as well as feature-packed games with stunning graphics and interactive gameplay.

Whether you’re a beginner or a casino enthusiast, there’s something for everyone.

play casino

The games are ready to play 24/7 and compatible with desktop computers and tablets alike.

You don’t need to install anything, so you can get started without hassle.

Site navigation is easy to use, making it simple to explore new games.

Join the fun, and dive into the excitement of spinning reels!

Платформа BlackSprut — это хорошо известная систем в теневом интернете, открывающая широкие возможности в рамках сообщества.

На платформе реализована простая структура, а визуальная часть понятен даже новичкам.

Участники ценят быструю загрузку страниц и жизнь на площадке.

bs2best.markets

Площадка разработана на комфорт и безопасность при навигации.

Если вы интересуетесь альтернативные цифровые пространства, BlackSprut может стать интересным вариантом.

Прежде чем начать лучше ознакомиться с базовые принципы анонимной сети.

Этот сайт — интернет-представительство лицензированного детективного агентства.

Мы организуем услуги по частным расследованиям.

Команда профессионалов работает с абсолютной дискретностью.

Мы берёмся за поиски людей и детальное изучение обстоятельств.

Детективное агентство

Каждое обращение рассматривается индивидуально.

Опираемся на эффективные инструменты и соблюдаем юридические нормы.

Ищете настоящих профессионалов — вы по адресу.

Наш веб-портал — интернет-представительство лицензированного сыскного бюро.

Мы предлагаем услуги по частным расследованиям.

Команда опытных специалистов работает с предельной этичностью.

Наша работа включает сбор информации и разные виды расследований.

Заказать детектива

Любой запрос получает персональный подход.

Мы используем проверенные подходы и работаем строго в рамках закона.

Если вы ищете ответственное агентство — добро пожаловать.

Данный ресурс — интернет-представительство независимого сыскного бюро.

Мы оказываем услуги в решении деликатных ситуаций.

Команда детективов работает с предельной осторожностью.

Мы занимаемся сбор информации и разные виды расследований.

Нанять детектива

Каждое обращение подходит с особым вниманием.

Опираемся на проверенные подходы и работаем строго в рамках закона.

Ищете ответственное агентство — свяжитесь с нами.

На данной платформе можно найти онлайн-игры от казино Vavada.

Каждый пользователь сможет выбрать подходящую игру — от традиционных игр до новейших моделей с бонусными раундами.

Платформа Vavada открывает широкий выбор проверенных автоматов, включая игры с джекпотом.

Каждый слот доступен без ограничений и подходит как для ПК, так и для мобильных устройств.

бонус вавада

Вы сможете испытать атмосферой игры, не выходя из квартиры.

Навигация по сайту понятна, что позволяет быстро найти нужную игру.

Присоединяйтесь сейчас, чтобы погрузиться в мир выигрышей!

Лето 2025 года обещает быть стильным и оригинальным в плане моды.

В тренде будут асимметрия и яркие акценты.

Цветовая палитра включают в себя чистые базовые цвета, создающие настроение.

Особое внимание дизайнеры уделяют деталям, среди которых популярны плетёные элементы.

https://telegra.ph/Armani-Exchange-gorodskoj-shik-s-italyanskim-harakterom-02-20

Возвращаются в моду элементы модерна, в свежем прочтении.

В стритстайле уже можно увидеть трендовые образы, которые впечатляют.

Не упустите шанс, чтобы чувствовать себя уверенно.

Here offers a great variety of interior clock designs for all styles.

You can browse minimalist and traditional styles to complement your living space.

Each piece is hand-picked for its design quality and accuracy.

Whether you’re decorating a cozy bedroom, there’s always a beautiful clock waiting for you.

best french style wall clocks

The collection is regularly updated with trending items.

We prioritize quality packaging, so your order is always in professional processing.

Start your journey to timeless elegance with just a few clicks.

Данный ресурс создан для трудоустройства по всей стране.

Вы можете найти актуальные предложения от проверенных работодателей.

На платформе появляются предложения в различных сферах.

Удалённая работа — вы выбираете.

https://my-articles-online.com/

Интерфейс сайта простой и подходит на широкую аудиторию.

Оставить отклик не потребует усилий.

Готовы к новым возможностям? — начните прямо сейчас.

Here, you can discover a wide selection of online slots from famous studios.

Players can enjoy traditional machines as well as new-generation slots with high-quality visuals and bonus rounds.

Even if you’re new or a seasoned gamer, there’s a game that fits your style.

money casino

All slot machines are available round the clock and designed for PCs and tablets alike.

No download is required, so you can jump into the action right away.

Platform layout is easy to use, making it simple to browse the collection.

Register now, and dive into the excitement of spinning reels!

Here, you can access a great variety of online slots from leading developers.

Visitors can enjoy retro-style games as well as new-generation slots with stunning graphics and interactive gameplay.

Even if you’re new or a seasoned gamer, there’s a game that fits your style.

play aviator

All slot machines are instantly accessible round the clock and compatible with laptops and mobile devices alike.

No download is required, so you can jump into the action right away.

The interface is user-friendly, making it quick to browse the collection.

Register now, and enjoy the excitement of spinning reels!

On this platform, you can find a great variety of online slots from famous studios.

Visitors can experience traditional machines as well as feature-packed games with vivid animation and bonus rounds.

Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned gamer, there’s something for everyone.

play casino

All slot machines are instantly accessible 24/7 and compatible with PCs and tablets alike.

All games run in your browser, so you can get started without hassle.

Platform layout is easy to use, making it simple to find your favorite slot.

Join the fun, and enjoy the excitement of spinning reels!

На этом сайте можно найти последние новости Краснодара.

Здесь собраны актуальные события города, репортажи и оперативная информация.

Будьте в курсе городских новостей и читайте только проверенные данные.

Если вам интересно, что нового в Краснодаре, заглядывайте сюда регулярно!

https://rftimes.ru/

Here, you can access lots of online slots from leading developers.

Visitors can experience traditional machines as well as feature-packed games with vivid animation and interactive gameplay.

If you’re just starting out or an experienced player, there’s a game that fits your style.

casino games

All slot machines are instantly accessible 24/7 and compatible with desktop computers and mobile devices alike.

All games run in your browser, so you can get started without hassle.

The interface is user-friendly, making it simple to browse the collection.

Join the fun, and dive into the thrill of casino games!

Did you know that nearly 50% of medication users commit preventable drug mistakes stemming from insufficient information?

Your physical condition should be your top priority. Every medication decision you consider plays crucial role in your quality of life. Staying educated about the drugs you take isn’t optional for successful recovery.

Your health depends on more than following prescriptions. Each drug changes your physiology in specific ways.

Consider these essential facts:

1. Mixing certain drugs can cause health emergencies

2. Seemingly harmless allergy medicines have strict usage limits

3. Altering dosages undermines therapy

To avoid risks, always:

✓ Research combinations using official tools

✓ Review guidelines in detail when starting new prescriptions

✓ Consult your doctor about proper usage

___________________________________

For reliable medication guidance, visit:

https://www.niftygateway.com/@imedix/

Our e-pharmacy provides an extensive variety of medications for budget-friendly costs.

You can find all types of medicines to meet your health needs.

We strive to maintain safe and effective medications without breaking the bank.

Quick and dependable delivery provides that your purchase arrives on time.

Experience the convenience of ordering medications online with us.

eriacta 100 how long does it last

The digital drugstore provides a wide range of pharmaceuticals with competitive pricing.

Customers can discover both prescription and over-the-counter drugs to meet your health needs.

We work hard to offer trusted brands without breaking the bank.

Quick and dependable delivery guarantees that your order is delivered promptly.

Experience the convenience of ordering medications online on our platform.

priligy dapoxetine india

Our platform features off-road vehicle rentals across the island.

Travelers may easily rent a vehicle for travel.

In case you’re looking to travel around coastal trails, a buggy is the fun way to do it.

https://www.provenexpert.com/buggycrete/

Our rides are safe and clean and can be rented for full-day plans.

On this platform is hassle-free and comes with great support.

Get ready to ride and feel Crete like never before.

On this site showcases multifunctional timepieces from reputable makers.

Browse through modern disc players with PLL tuner and dual wake options.

Most units include auxiliary inputs, charging capability, and power outage protection.

This collection spans economical models to luxury editions.

best cd alarm clock radio

All devices offer snooze functions, night modes, and digital displays.

Order today via direct Walmart links with free shipping.

Discover the perfect clock-radio-CD setup for home everyday enjoyment.

Here, you can discover a wide selection of casino slots from leading developers.

Users can experience traditional machines as well as feature-packed games with stunning graphics and bonus rounds.

If you’re just starting out or an experienced player, there’s always a slot to match your mood.

slot casino

All slot machines are ready to play round the clock and designed for laptops and tablets alike.

All games run in your browser, so you can start playing instantly.

Site navigation is user-friendly, making it simple to explore new games.

Sign up today, and enjoy the thrill of casino games!

Приобретение страховки перед поездкой за рубеж — это необходимая мера для защиты здоровья путешественника.

Страховка включает неотложную помощь в случае несчастного случая за границей.

Помимо этого, страховка может охватывать компенсацию на транспортировку.

расчет каско

Некоторые государства настаивают на наличие страховки для получения визы.

При отсутствии полиса госпитализация могут привести к большим затратам.

Покупка страховки перед выездом

This platform offers you the chance to find experts for temporary high-risk tasks.

Users can easily request assistance for specialized situations.

All workers are trained in managing complex operations.

hitman-assassin-killer.com

Our platform guarantees secure connections between employers and contractors.

For those needing immediate help, this platform is here for you.

Create a job and find a fit with a professional today!

Questa pagina consente la selezione di lavoratori per attività a rischio.

Gli utenti possono trovare esperti affidabili per missioni singole.

Le persone disponibili sono valutati con attenzione.

ordina l’uccisione

Con il nostro aiuto è possibile visualizzare profili prima di procedere.

La sicurezza è un nostro valore fondamentale.

Contattateci oggi stesso per ottenere aiuto specializzato!

В этом разделе вы можете перейти на действующее зеркало 1хБет без трудностей.

Систематически обновляем зеркала, чтобы облегчить беспрепятственный доступ к платформе.

Открывая резервную копию, вы сможете пользоваться всеми функциями без перебоев.

1xbet-official.live

Эта страница обеспечит возможность вам безопасно получить свежее зеркало 1 икс бет.

Мы следим за тем, чтобы любой игрок смог получить полный доступ.

Не пропустите обновления, чтобы не терять доступ с 1xBet!

Этот сайт — подтверждённый интернет-бутик Bottega Veneta с отправкой по стране.

На нашем сайте вы можете оформить заказ на фирменную продукцию Боттега Венета с гарантией подлинности.

Любая покупка имеют гарантию качества от производителя.

bottega-official.ru

Доставка осуществляется оперативно в любой регион России.

Платформа предлагает разные варианты платежей и гарантию возврата средств.

Положитесь на официальном сайте Боттега Венета, чтобы чувствовать уверенность в покупке!

在此页面,您可以聘请专门从事临时的高危工作的执行者。

我们汇集大量可靠的工作人员供您选择。

无论需要何种复杂情况,您都可以轻松找到理想的帮手。

雇佣一名杀手

所有执行者均经过审核,保证您的安全。

服务中心注重效率,让您的特殊需求更加无忧。

如果您需要服务详情,请立即联系!

На этом сайте вы обнаружите всю информацию о реферальной системе: 1win.

Здесь размещены все детали взаимодействия, правила присоединения и возможные бонусы.

Любой блок четко изложен, что помогает быстро усвоить в нюансах функционирования.

Плюс ко всему, имеются ответы на частые вопросы и подсказки для начинающих.

Материалы поддерживаются в актуальном состоянии, поэтому вы можете быть уверены в достоверности предоставленных материалов.

Источник поможет в понимании партнёрской программы 1Win.

Our service makes it possible to connect with specialists for occasional high-risk tasks.

Users can securely arrange assistance for specialized requirements.

All contractors are trained in managing sensitive activities.

hitman for hire

This service guarantees private interactions between employers and freelancers.

For those needing urgent assistance, the site is the perfect place.

List your task and match with an expert instantly!

Questa pagina permette l’assunzione di lavoratori per compiti delicati.

Gli utenti possono trovare operatori competenti per lavori una tantum.

Tutti i lavoratori sono valutati con severi controlli.

assumi assassino

Sul sito è possibile ottenere informazioni dettagliate prima della scelta.

La fiducia continua a essere la nostra priorità.

Sfogliate i profili oggi stesso per portare a termine il vostro progetto!

Looking to connect with qualified contractors ready to handle temporary hazardous tasks.

Require a specialist for a high-risk task? Discover certified experts on our platform for critical dangerous work.

rent a killer

This website connects employers with licensed workers prepared to take on unsafe short-term positions.

Employ verified laborers to perform perilous jobs efficiently. Perfect when you need emergency assignments demanding safety-focused labor.

Here, you can access a great variety of online slots from famous studios.

Visitors can enjoy classic slots as well as feature-packed games with high-quality visuals and interactive gameplay.

Even if you’re new or a casino enthusiast, there’s always a slot to match your mood.

casino slots

The games are ready to play anytime and optimized for laptops and smartphones alike.

No download is required, so you can get started without hassle.

The interface is intuitive, making it simple to find your favorite slot.

Sign up today, and discover the excitement of spinning reels!

People contemplate taking their own life for a variety of reasons, frequently stemming from deep emotional pain.

The belief that things won’t improve may consume their desire to continue. In many cases, loneliness is a major factor in this decision.

Conditions like depression or anxiety distort thinking, preventing someone to see alternatives to their pain.

how to commit suicide

Life stressors can also push someone to consider drastic measures.

Lack of access to help can make them feel stuck. Keep in mind seeking assistance can save lives.

访问者请注意,这是一个仅限成年人浏览的站点。

进入前请确认您已年满成年年龄,并同意遵守当地法律法规。

本网站包含成人向资源,请自行判断是否适合进入。 色情网站。

若不接受以上声明,请立即停止访问。

我们致力于提供健康安全的网络体验。

This resource you can discover particular special offers for a renowned betting brand.

The selection of rewarding options is periodically revised to confirm that you always have availability of the modern bargains.

Via these coupons, you can save substantially on your wagers and multiply your options of gaining an edge.

Every coupon are thoroughly verified for genuineness and efficiency before showing up.

https://clearbridgetech.com/pages/pod_flagom_kluba_drughina.html

Plus, we offer extensive details on how to activate each promo code to optimize your benefits.

Take into account that some proposals may have particular conditions or restricted periods, so it’s critical to scrutinize carefully all the aspects before utilizing them.

Our platform provides a large selection of medications for home delivery.

Anyone can conveniently buy treatments from your device.

Our product list includes standard solutions and more specific prescriptions.

Each item is provided by verified suppliers.

oral jelly kamagra

We maintain discreet service, with encrypted transactions and fast shipping.

Whether you’re managing a chronic condition, you’ll find affordable choices here.

Begin shopping today and get reliable support.

This website provides a wide range of prescription drugs for home delivery.

Users can conveniently order essential medicines from your device.

Our product list includes both common solutions and more specific prescriptions.

Each item is provided by reliable providers.

tadapox tadalafil dapoxetine 80mg

We maintain quality and care, with data protection and fast shipping.

Whether you’re looking for daily supplements, you’ll find trusted options here.

Begin shopping today and get stress-free healthcare delivery.

1XBet Bonus Code – Exclusive Bonus maximum of €130

Enter the 1xBet bonus code: Code 1XBRO200 while signing up via the application to access special perks given by 1XBet and get welcome bonus maximum of a full hundred percent, for sports betting and a casino bonus featuring free spin package. Open the app followed by proceeding through the sign-up process.

The 1XBet promotional code: 1xbro200 offers an amazing starter bonus for first-time users — a complete hundred percent as much as $130 once you register. Promotional codes are the key to unlocking bonuses, plus 1XBet’s promo codes are no exception. After entering this code, players can take advantage of various offers in various phases of their betting experience. Although you’re not eligible for the welcome bonus, 1xBet India guarantees its devoted players are rewarded via ongoing deals. Look at the Deals tab on the site frequently to remain aware regarding recent promotions tailored for existing players.

promo code for 1xbet india

What 1xBet bonus code is currently active right now?

The promotional code applicable to 1XBet stands as 1XBRO200, which allows first-time users registering with the gambling provider to access an offer amounting to €130. To access exclusive bonuses for casino and wagering, please input our bonus code related to 1XBET while filling out the form. To take advantage from this deal, potential customers need to type the bonus code 1XBET during the registration procedure to receive a 100% bonus on their initial deposit.

Here, you can easily find live video chats.

Searching for engaging dialogues career-focused talks, this platform has options for any preference.

The video chat feature developed for bringing users together across different regions.

With high-quality video along with sharp sound, each interaction feels natural.

You can join public rooms initiate one-on-one conversations, depending on your preferences.

https://erovideochat.pw/

The only thing needed consistent online access plus any compatible tool begin chatting.

Keep working ,fantastic job!

В данной платформе представлены видеообщение в реальном времени.

Вы хотите увлекательные диалоги или профессиональные связи, здесь есть варианты для всех.

Этот инструмент предназначена чтобы объединить пользователей из разных уголков планеты.

порно секс чат

За счет четких изображений и превосходным звуком, каждый разговор остается живым.

Войти в открытые чаты или начать личный диалог, опираясь на ваших предпочтений.

Единственное условие — надежная сеть и совместимое устройство, и вы сможете подключиться.

This website, you can discover a wide selection of slot machines from leading developers.

Visitors can try out classic slots as well as feature-packed games with stunning graphics and exciting features.

Even if you’re new or a seasoned gamer, there’s a game that fits your style.

sweet bonanza

All slot machines are ready to play round the clock and optimized for desktop computers and smartphones alike.

You don’t need to install anything, so you can get started without hassle.

Platform layout is intuitive, making it simple to find your favorite slot.

Sign up today, and enjoy the thrill of casino games!

Here, find a variety internet-based casino sites.

Whether you’re looking for traditional options latest releases, you’ll find an option to suit all preferences.

All featured casinos fully reviewed for trustworthiness, allowing users to gamble securely.

casino

What’s more, the site offers exclusive bonuses along with offers for new players as well as regulars.

Thanks to user-friendly browsing, discovering a suitable site takes just moments, saving you time.

Stay updated regarding new entries with frequent visits, because updated platforms are added regularly.

这个网站 提供 海量的 成人内容,满足 成年访客 的 需求。

无论您喜欢 哪种类型 的 影片,这里都 应有尽有。

所有 资源 都经过 严格审核,确保 高质量 的 观看体验。

A片

我们支持 各种终端 访问,包括 手机,随时随地 畅享内容。

加入我们,探索 激情时刻 的 两性空间。

Aviator blends air travel with high stakes.

Jump into the cockpit and try your luck through turbulent skies for huge multipliers.

With its vintage-inspired design, the game reflects the spirit of aircraft legends.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/robin-kh-150138202_aviator-game-download-activity-7295792143506321408-81HD/

Watch as the plane takes off – cash out before it flies away to secure your winnings.

Featuring seamless gameplay and dynamic audio design, it’s a must-try for slot enthusiasts.

Whether you’re testing luck, Aviator delivers endless thrills with every flight.

This flight-themed slot combines air travel with exciting rewards.

Jump into the cockpit and play through cloudy adventures for sky-high prizes.

With its retro-inspired design, the game captures the spirit of aircraft legends.

aviator betting game download

Watch as the plane takes off – cash out before it flies away to secure your winnings.

Featuring instant gameplay and immersive sound effects, it’s a favorite for slot enthusiasts.

Whether you’re testing luck, Aviator delivers endless excitement with every flight.

This flight-themed slot blends exploration with exciting rewards.

Jump into the cockpit and try your luck through cloudy adventures for huge multipliers.

With its retro-inspired visuals, the game evokes the spirit of aircraft legends.

aviator game download link

Watch as the plane takes off – withdraw before it disappears to grab your winnings.

Featuring smooth gameplay and immersive audio design, it’s a favorite for casual players.

Whether you’re chasing wins, Aviator delivers non-stop action with every round.

Luxury horology never lose relevance for many compelling factors.

Their artistic design and legacy distinguish them from others.

They symbolize power and exclusivity while blending functionality with art.

Unlike digital gadgets, their value grows over time due to rarity and durability.

https://github.com/MaxBezelCOM

Collectors and enthusiasts treasure the engineering marvels that modern tech cannot imitate.

For many, collecting them defines passion that goes beyond fashion.

There is noticeably a bundle to know about this. I think you made some good points in features also.

Трендовые фасоны сезона нынешнего года отличаются разнообразием.

В тренде стразы и пайетки из полупрозрачных тканей.

Блестящие ткани придают образу роскоши.

Греческий стиль с драпировкой возвращаются в моду.

Разрезы на юбках создают баланс между строгостью и игрой.

Ищите вдохновение в новых коллекциях — детали и фактуры оставят в памяти гостей!

https://forum.elonx.cz/viewtopic.php?f=11&t=15122

Модные образы для торжеств этого сезона вдохновляют дизайнеров.

Актуальны кружевные рукава и корсеты из полупрозрачных тканей.

Детали из люрекса делают платье запоминающимся.

Многослойные юбки возвращаются в моду.

Разрезы на юбках подчеркивают элегантность.

Ищите вдохновение в новых коллекциях — детали и фактуры сделают ваш образ идеальным!

https://naphopibun.go.th/forum/suggestion-box/931050-u-lini-sv-d-bni-pl-ija-e-g-g-d-s-v-i-p-vib-ru

I wish to express my passion for your kindness giving support to persons that actually need guidance on this important issue. Your real commitment to getting the message across became exceedingly informative and have regularly permitted professionals much like me to arrive at their desired goals. Your entire interesting facts can mean a great deal a person like me and even more to my office colleagues. Best wishes; from all of us.

The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak 16202ST features a elegant 39mm stainless steel case with an ultra-thin profile of just 8.1mm thickness, housing the advanced Calibre 7121 movement. Its striking “Bleu nuit nuage 50” dial showcases a signature Petite Tapisserie pattern, fading from golden hues to deep black edges for a dynamic aesthetic. The octagonal bezel with hexagonal screws pays homage to the original 1972 design, while the scratch-resistant sapphire glass ensures clear visibility.

https://telegra.ph/Audemars-Piguet-Royal-Oak-16202ST-A-Legacy-of-Innovation-and-Craftsmanship-06-02

Water-resistant to 50 meters, this “Jumbo” model balances robust performance with luxurious refinement, paired with a steel link strap and secure AP folding clasp. A contemporary celebration of classic design, the 16202ST embodies Audemars Piguet’s innovation through its meticulous mechanics and evergreen Royal Oak DNA.

¿Buscas cupones vigentes de 1xBet? En este sitio descubrirás recompensas especiales para tus jugadas.

El código 1x_12121 te da acceso a 6500 RUB para nuevos usuarios.

Además , utiliza 1XRUN200 y disfruta una oferta exclusiva de €1500 + 150 giros gratis.

https://spencerpiym42197.muzwiki.com/7715633/descubre_cómo_usar_el_código_promocional_1xbet_para_apostar_free_of_charge_en_argentina_méxico_chile_y_más

Revisa las novedades para acumular recompensas adicionales .

Todos los códigos son verificados para esta semana.

¡Aprovecha y maximiza tus ganancias con esta plataforma confiable!

На данном сайте вы можете отыскать боту “Глаз Бога” , который может проанализировать всю информацию о любом человеке из открытых источников .

Данный сервис осуществляет анализ фото и раскрывает данные из соцсетей .

С его помощью можно пробить данные через официальный сервис , используя автомобильный номер в качестве поискового запроса .

пробив тг

Система “Глаз Бога” автоматически собирает информацию из открытых баз , формируя подробный отчет .

Подписчики бота получают ограниченное тестирование для проверки эффективности.

Платформа постоянно развивается, сохраняя актуальность данных в соответствии с законодательством РФ.

Сертификация и лицензии — ключевой аспект ведения бизнеса в России, обеспечивающий защиту от непрофессионалов.

Декларирование продукции требуется для подтверждения соответствия стандартам.

Для 49 видов деятельности необходимо специальных разрешений.

https://ok.ru/group/70000034956977/topic/158860235421873

Игнорирование требований ведут к приостановке деятельности.

Дополнительные лицензии помогает усилить конкурентоспособность бизнеса.

Соблюдение норм — залог успешного развития компании.

Здесь вы можете получить доступ к боту “Глаз Бога” , который позволяет проанализировать всю информацию о любом человеке из публичных данных.

Этот мощный инструмент осуществляет поиск по номеру телефона и предоставляет детали из онлайн-платформ.

С его помощью можно узнать контакты через официальный сервис , используя автомобильный номер в качестве поискового запроса .

проверить машину по номеру

Алгоритм “Глаз Бога” автоматически анализирует информацию из множества источников , формируя структурированные данные .

Клиенты бота получают ограниченное тестирование для проверки эффективности.

Решение постоянно развивается, сохраняя высокую точность в соответствии с стандартами безопасности .

На данном сайте можно получить мессенджер-бот “Глаз Бога”, который собрать сведения о гражданине из открытых источников.

Инструмент работает по фото, анализируя актуальные базы в Рунете. Благодаря ему можно получить пять пробивов и глубокий сбор по запросу.

Инструмент проверен согласно последним данным и поддерживает фото и видео. Бот сможет найти профили в соцсетях и покажет информацию за секунды.

https://glazboga.net/

Данный сервис — идеальное решение в анализе персон через Telegram.

Searching for special 1xBet promo codes ? This platform is your go-to resource to access valuable deals designed to boost your wagers.

Whether you’re a new user or a seasoned bettor , our curated selection ensures maximum benefits for your first deposit .

Stay updated on weekly promotions to multiply your rewards.

https://684188cd3ab96.site123.me/

All listed codes are frequently updated to ensure functionality for current users.

Act now of exclusive perks to transform your betting strategy with 1xBet.

замена венцов новокузнецк

На данном сайте доступен мессенджер-бот “Глаз Бога”, который проверить сведения о гражданине через открытые базы.

Бот работает по ФИО, обрабатывая актуальные базы онлайн. С его помощью можно получить 5 бесплатных проверок и глубокий сбор по фото.

Инструмент обновлен на 2025 год и включает аудио-материалы. Бот сможет узнать данные по госреестрам и отобразит сведения за секунды.

https://glazboga.net/

Это бот — помощник при поиске людей удаленно.

Looking for exclusive 1xBet coupon codes ? Our website is your best choice to unlock rewarding bonuses for betting .

Whether you’re a new user or an experienced player, verified codes ensures enhanced rewards across all bets.

Keep an eye on weekly promotions to maximize your winning potential .

https://list.ly/burkebates26jvpjpd

All listed codes are regularly verified to ensure functionality in 2025 .

Don’t miss out of exclusive perks to revolutionize your odds of winning with 1xBet.

Прямо здесь вы найдете сервис “Глаз Бога”, что найти сведения о человеке по публичным данным.

Сервис работает по номеру телефона, обрабатывая публичные материалы в сети. Через бота осуществляется бесплатный поиск и полный отчет по имени.

Инструмент обновлен на август 2024 и включает фото и видео. Бот поможет узнать данные по госреестрам и отобразит результаты в режиме реального времени.

https://glazboga.net/

Это бот — выбор в анализе персон удаленно.

Обязательная сертификация в России критически важна для подтверждения качества потребителей, так как позволяет исключить опасной или некачественной продукции на рынок.

Система сертификации основаны на федеральных законах , таких как ФЗ № 184-ФЗ, и контролируют как отечественные товары, так и импортные аналоги .

Стоимость ИСО 9001 Официальная проверка гарантирует, что продукция прошла тестирование безопасности и не нанесет вреда людям и окружающей среде.

Важно отметить сертификация усиливает конкурентоспособность товаров на международном уровне и упрощает к экспорту.

Развитие системы сертификации отражает современным стандартам, что укрепляет экономику в условиях технологических вызовов.

замена венцов новокузнецк

This website features comprehensive information about Audemars Piguet Royal Oak watches, including price ranges and model details .

Discover data on iconic models like the 41mm Selfwinding in stainless steel or white gold, with prices starting at $28,600 .

The platform tracks secondary market trends , where limited editions can sell for $140,000+ .

Audemars Royal Oak 15500 prices

Movement types such as water resistance are clearly outlined .

Stay updated on 2025 price fluctuations, including the Royal Oak 15510ST’s investment potential.

Здесь вы можете найти актуальными новостями регионов и глобального масштаба.

Информация поступает ежеминутно .

Представлены фоторепортажи с мест событий .

Экспертные комментарии помогут понять контекст .

Контент предоставляется в режиме онлайн.

https://omskdaily.ru

ремонт фундамента кемерово

Discover detailed information about the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore 15710ST on this site , including pricing insights ranging from $34,566 to $36,200 for stainless steel models.

The 42mm timepiece boasts a robust design with mechanical precision and rugged aesthetics, crafted in stainless steel .

https://ap15710st.superpodium.com

Analyze secondary market data , where limited editions fluctuate with demand, alongside rare references from the 1970s.

View real-time updates on availability, specifications, and historical value, with free market analyses for informed decisions.

Looking for latest 1xBet promo codes? This site offers working bonus codes like 1x_12121 for registrations in 2025. Claim €1500 + 150 FS as a welcome bonus.

Use official promo codes during registration to maximize your bonuses. Enjoy no-deposit bonuses and special promotions tailored for casino games.

Discover monthly updated codes for 1xBet Kazakhstan with fast withdrawals.

All voucher is checked for validity.

Don’t miss exclusive bonuses like GIFT25 to double your funds.

Valid for first-time deposits only.

https://textualheritage.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=3973

Enjoy seamless benefits with easy redemption.

Лицензирование и сертификация — обязательное условие ведения бизнеса в России, гарантирующий защиту от непрофессионалов.

Декларирование продукции требуется для подтверждения безопасности товаров.

Для торговли, логистики, финансов необходимо получение лицензий.

https://ok.ru/group/70000034956977/topic/158835151321265

Игнорирование требований ведут к приостановке деятельности.

Дополнительные лицензии помогает повысить доверие бизнеса.

Своевременное оформление — залог успешного развития компании.

подъем дома новокузнецк

ремонт фундамента новокузнецк

Ищете ресурсы для нумизматов ? Эта платформа предлагает всё необходимое погружения в тему нумизматики!

У нас вы найдёте коллекционные экземпляры из исторических периодов, а также драгоценные находки.

Просмотрите архив с подробными описаниями и детальными снимками, чтобы сделать выбор .

георгий победоносец монета 50 рублей золото

Для новичков или эксперт, наши статьи и руководства помогут углубить экспертизу.

Воспользуйтесь возможностью добавить в коллекцию эксклюзивные артефакты с гарантией подлинности .

Присоединяйтесь сообщества энтузиастов и будьте в курсе последних новостей в мире нумизматики.

Launched in 1999, Richard Mille revolutionized luxury watchmaking with cutting-edge innovation . The brand’s iconic timepieces combine aerospace-grade ceramics and sapphire to balance durability .

Drawing inspiration from the aerodynamics of Formula 1, each watch embodies “form follows function”, ensuring lightweight comfort . Collections like the RM 001 Tourbillon set new benchmarks since their debut.

Richard Mille’s experimental research in mechanical engineering yield skeletonized movements tested in extreme conditions .

True Mille Richard RM 6702 watch

Rooted in innovation, the brand pushes boundaries through bespoke complications for collectors .

With a legacy , Richard Mille epitomizes luxury fused with technology , captivating discerning enthusiasts .

Discover the iconic Patek Philippe Nautilus, a luxury timepiece that blends athletic sophistication with exquisite craftsmanship .

Launched in 1976 , this legendary watch revolutionized high-end sports watches, featuring signature angular cases and horizontally grooved dials .

For stainless steel variants like the 5990/1A-011 with a 55-hour energy retention to luxurious white gold editions such as the 5811/1G-001 with a azure-toned face, the Nautilus caters to both avid enthusiasts and casual admirers.

Authentic Patek Nautilus 5980r wristwatches

Certain diamond-adorned versions elevate the design with gemstone accents, adding unmatched glamour to the iconic silhouette .

According to recent indices like the 5726/1A-014 at ~$106,000, the Nautilus remains a prized asset in the world of premium watchmaking.

Whether you seek a historical model or contemporary iteration , the Nautilus embodies Patek Philippe’s tradition of innovation.

Die Royal Oak 16202ST kombiniert ein rostfreies Stahlgehäuse von 39 mm mit einem extraflachen Gehäuse von nur 8,1 mm Dicke.

Ihr Herzstück bildet das neue Kaliber 7121 mit 55 Stunden Gangreserve.

Der smaragdene Farbverlauf des Zifferblatts wird durch das feine Guillochierungen und die kratzfeste Saphirscheibe mit Antireflexbeschichtung betont.

Neben klassischer Zeitmessung bietet die Uhr ein Datumsfenster bei 3 Uhr.

audemar 15202

Die 50-Meter-Wasserdichte macht sie alltagstauglich.

Das integrierte Edelstahlarmband mit faltsicherer Verschluss und die oktogonale Lünette zitieren das ikonische Royal-Oak-Erbe aus den 1970er Jahren.

Als Teil der „Jumbo“-Kollektion verkörpert die 16202ST meisterliche Uhrmacherkunst mit einem aktuellen Preis ab ~75.900 €.

Двустенные резервуары обеспечивают защиту от утечек, а подземные модификации подходят для разных условий.

Заводы предлагают индивидуальные проекты объемом до 500 м³ с монтажом под ключ.

Варианты слов и фраз соответствуют данным из (давление), (материалы), (типы резервуаров), (защита), и (производство).

https://zso-k.ru/product/emkosti-podzemnye/emkosti-drenazhnye-uteplyonnye/emkost-drenazhnaya-30-m3-uteplennaya/

Проверена орфография (напр., “нефтепродукты”, “мазут”) и техническая точность (напр., “двустенные” для экологичности).

Структура сохраняет логику: описание, конструкция, применение, особенности, производство.

Стальные резервуары используются для сбора нефтепродуктов и соответствуют стандартам давления до 0,04 МПа.

Вертикальные емкости изготавливают из нержавеющих сплавов с антикоррозийным покрытием.

Идеальны для АЗС: хранят бензин, керосин, мазут или авиационное топливо.

Подземный пожарный резервуар 50 м3

Двустенные резервуары обеспечивают экологическую безопасность, а наземные установки подходят для разных условий.

Заводы предлагают индивидуальные проекты объемом до 500 м³ с монтажом под ключ.

Die Royal Oak 16202ST vereint ein 39-mm-Edelstahlgehäuse mit einem nur 8,1 mm dünnen Bauweise und dem automatischen Werk 7121 für lange Energieautonomie.

Das „Bleu Nuit“-Zifferblatt mit Weißgold-Indexen und Royal-Oak-Zeigern wird durch eine Saphirglas-Scheibe mit Antireflex-Beschichtung geschützt.

Neben Datum bei 3 Uhr bietet die Uhr 50-Meter-Wasserdichte und ein geschlossenes Edelstahlband mit verstellbarem Verschluss.

Piguet Audemars Royal Oak 15450st armbanduhr

Die oktogonale Lünette mit ikonenhaften Hexschrauben und die gebürstete Oberflächenkombination zitieren den legendären Genta-Entwurf.

Als Teil der Extra-Thin-Kollektion ist die 16202ST eine horlogerie-Perle mit einem Wertsteigerungspotenzial.

Premium mechanical timepieces remain popular for multiple essential causes.

Their artistic design and legacy set them apart.

They symbolize power and exclusivity while merging practicality and style.

Unlike digital gadgets, they endure through generations due to artisanal creation.

https://unsplash.com/@arabicbezel

Collectors and enthusiasts admire the intricate movements that no smartwatch can replicate.

For many, possessing them means legacy that goes beyond fashion.

Наш ресурс предлагает интересные новости со всего мира.

Здесь доступны новости о политике, технологиях и разнообразных темах.

Новостная лента обновляется в режиме реального времени, что позволяет всегда быть в курсе.

Понятная навигация помогает быстро ориентироваться.

https://miramoda.ru

Любой материал предлагаются с фактчеком.

Редакция придерживается объективности.

Следите за обновлениями, чтобы быть всегда информированными.

Стальные резервуары используются для сбора нефтепродуктов и соответствуют стандартам давления до 0,04 МПа.

Вертикальные емкости изготавливают из нержавеющих сплавов с антикоррозийным покрытием.

Идеальны для АЗС: хранят бензин, керосин, мазут или биодизель.

https://zso-k.ru/product/emkosti-podzemnye/emkosti-pozharnye/emkost-pozharnaya-90-m3/

Двустенные резервуары обеспечивают экологическую безопасность, а подземные модификации подходят для разных условий.

Заводы предлагают типовые решения объемом до 500 м³ с монтажом под ключ.

Установка видеокамер обеспечит безопасность территории круглосуточно.

Современные технологии обеспечивают высокое качество изображения даже при слабом освещении.

Наша компания предоставляет различные варианты оборудования, подходящих для дома.

установка видеонаблюдения в лифте

Грамотная настройка и техническая поддержка превращают решение максимально удобным для любых задач.

Свяжитесь с нами, для получения оптимальное предложение для установки видеонаблюдения.

На данном сайте доступен Telegram-бот “Глаз Бога”, позволяющий проверить сведения о гражданине через открытые базы.

Сервис работает по ФИО, обрабатывая публичные материалы в сети. Благодаря ему можно получить 5 бесплатных проверок и полный отчет по запросу.

Инструмент обновлен на 2025 год и охватывает аудио-материалы. Глаз Бога поможет проверить личность по госреестрам и предоставит информацию мгновенно.

глаз бога телеграм бесплатно

Такой сервис — помощник в анализе граждан через Telegram.

À la recherche de divertissements interactifs? Notre plateforme regroupe des centaines de titres pour tous les goûts .

Des puzzles aux défis multijoueurs , plongez des mécaniques innovantes directement depuis votre navigateur.

Découvrez les nouveautés comme le Sudoku ou des aventures dynamiques en solo .

Les amateurs de sport, des courses automobiles en 3D réaliste vous attendent.

casino en ligne france

Accédez gratuitement de mises à jour régulières et connectez-vous une communauté active .

Que vous préfériez l’action, cette bibliothèque virtuelle deviendra votre destination préférée .

Современные механические часы сочетают вековые традиции с высокоточными материалами, такими как титан и сапфировое стекло.

Прозрачные задние крышки из сапфирового кристалла позволяют любоваться механизмом в действии.

Маркировка с Super-LumiNova обеспечивает яркую подсветку, сохраняя эстетику циферблата.

https://chrono.luxepodium.com/blog/584-tudor-black-bay-master-chronometer-a-classic-dive-watch-in-monochrome/

Модели вроде Patek Philippe Nautilus дополняют хронографами и турбийонами.

Часы с роторным механизмом не требуют батареек, преобразуя кинетическую энергию в запас хода до 70 часов.

?Hola, jugadores entusiastas !

Juega sin fronteras en casinos fuera de EspaГ±a – https://casinosonlinefueradeespanol.xyz/# casinosonlinefueradeespanol

?Que disfrutes de asombrosas exitos sobresalientes !

Этот бот поможет получить информацию по заданному профилю.

Достаточно ввести никнейм в соцсетях, чтобы сформировать отчёт.

Система анализирует публичные данные и активность в сети .

бот глаз бога информация

Результаты формируются в реальном времени с проверкой достоверности .

Идеально подходит для проверки партнёров перед важными решениями.

Конфиденциальность и точность данных — наш приоритет .

Хотите собрать данные о человеке ? Этот бот поможет полный профиль в режиме реального времени .

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для поиска публичных записей в открытых источниках.

Узнайте контактные данные или интересы через автоматизированный скан с гарантией точности .

глаз бога официальный сайт

Система функционирует в рамках закона , обрабатывая открытые данные .

Получите детализированную выжимку с геолокационными метками и графиками активности .

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для исследований — точность гарантирована!

Хотите найти данные о пользователе? Наш сервис поможет детальный отчет мгновенно.

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для анализа цифровых следов в открытых источниках.

Выясните место работы или активность через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

тг канал глаз бога

Система функционирует с соблюдением GDPR, используя только открытые данные .

Получите расширенный отчет с историей аккаунтов и списком связей.

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для digital-расследований — точность гарантирована!

Этот бот поможет получить информацию по заданному профилю.

Достаточно ввести никнейм в соцсетях, чтобы получить сведения .

Система анализирует публичные данные и активность в сети .

глаз бога проверить

Результаты формируются мгновенно с проверкой достоверности .

Оптимален для проверки партнёров перед сотрудничеством .