SATURDAY JANUARY 10, 1914

HARRY FRAGSON’S FUNERAL. – DISORDERLY SCENES.

Disgraceful scenes marred the funeral of Harry Fragson the murdered music hall entertainer, which took place in Paris on Saturday. Owing to the inadequacy of the attendant police to control the crowd, great confusion was caused, and some of the people behaved in a very unseemly manner. At the cemetery at Montmartre, the religious rites had to be curtailed owing to the conduct of the public.

MONDAY 29 JUNE, 1914

AUSTRIAN HEIR ASSASSINATED. Shot Dead by Servian Student. WIFE MURDERED. Tragedy in the Capital of Bosnia. DUCHESS’S HEROISM. Threw Herself Across Her Husband’s Body.

Once again the assassin has plunged the Austrian Imperial family into mourning.

The Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Heir Presumptive to the Imperial Throne, and his morganatic wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated yesterday in the streets of Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, to which city he had gone in connection with the manoeuvres.

Earlier in the day, when the Archduke and Duchess were driving in a motor-car to the Town Hall, a bomb was thrown at the vehicle, but its occupants escaped without injury. After a reception at the Town Hall the Archducal party left for the Museum.

On the way an eighteen-year-old Servian student, named Prinzip, threw a bomb and then fired and hit, first, the Archduke and then the Duchess. The motorcar drove to the Konak, where medical aid was procured, but both the Archduke and Duchess succumbed to their injuries.

Both the thrower of the first bomb and the murderer were arrested. The thrower of the first bomb, a printer, named Gabrinovitch, has also been been taken into custody.

It is believed that the plot is of Servian origin and that many persons are involved in it.

The aged Emperor returned to Vienna today from Ischl, whither he had gone for the summer.

By the tragedy the Archduke Karl Franz Joseph, the late Archduke’s nephew, becomes heir to the Throne.

The murdered Archduke and the Duchess were guests of the King and Queen at Windsor last November, and during their stay in this country visited the Duke and Duchess of Portland at Welbeck.

WEDNESDAY JULY 29, 1914

WAR, RED WAR.

Austria has lost no time in declaring war against Servia, and has thereby incalculably increased the difficulties of statesmen like Sir Edward Grey who are toiling to prevent a general conflagration. History repeats itself, and the policy of repression by which Vienna tried half a century ago to keep down northern Italy is being applied in the same way to crush Slav aspirations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, The provocation from Belgrade has been intolerable, but the reparation demanded is unmeasured, The Austrian calculation is no doubt to get Servia bound and helpless before any interference is possible on her behalf, but she cannot inflame the whole spirit of Panslavism without Russia coming to the rescue. At that point the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente are liable to be drawn into the fray, hateful as it must be to all the traditions of Italian national sentiment to aid in the designs of her old oppressor Austria. The German Emperor is probably as earnest an influence on the side of peace as are France and England. Financial considerations should weigh heavily with all the Powers to maintain peace, but unfortunately when the war fever burns these are never thought of. The best that could happen, even for Servia herself, is that she should be swiftly beaten to her knees, because then Europe mi’ght interpose secure peace. At present there are limits to the disasters which may ensue.

AUGUST 1, 1914

AMERICAN EMBASSY AS NEUTRAL CENTRE

Mr. Gerard, in Event of War, Will Protect British and French Interests in Berlin. SCRAMBLE FOR PASSPORTS But Hotels Reap Unexpected Harvest Owing to Americans’ Desire to See German “War Lords.”

BERLIN, July 31. — Ambassador Gerard’s American vacation plans have been abruptly hung up by the European political complications. Mr. Gerard planned to leave Berlin at the end of this week for a ten days’ sojourn in Venice, then to return to Germany and sail on the Vaterland on Aug. 12; but he has now decided not to go away while the situation bristles with danger.

If a general European war starts, of course, the ambassador will abandon all thought of going to the United States. The American Embassy in Berlin would in that event be practically the only independent diplomatic establishment of the first rank left in the German capital. Mr. Gerard would undoubtedly be entrusted with the representation of England’s and France’s interests and the protection of their respective subjects and citizens, in the same way that Mr. Washburn, the American Minister to France during the siege of Paris, looked after the interests of Germany.

If Armageddon comes, the embassies of Russia, France, and great Britain in Berlin would, of course, immediately close their shutters. The embassies of Austria and Italy, as allies of Germany, would remain open.

Even Russia might ask Uncle Sam to look after her interests here, as the only other diplomatic establishments of embassy rank are those of Japan, Turkey, and Spain, which would hardly come into consideration.

Mr. Gerard has been keeping in constant touch hourly with developments. The ambassador has had frequent conferences at the Foreign Office, and, owing to his pleasant personal relations with the ambassadors both of the Triple Alliance and Triple Entente powers, has been in a unique position, being able to learn the views inspiring each of the rival groups.

Mrs. Gerard probably intends, if it is possible, to a dear to her plan to sail on Aug. 12. She will proceed directly to Montana to her paternal ranch, where she never fails to spend the summer holidays.

The embassy has done a land-office business in issuing passports this week, tourists who never before felt the necessity of such documents investing $2 apiece in engraved papers which bespeak the protection and assistance of foreign governments for United States wayfarers. James Speyer of New York was one of the first applicants for passports.

A “How are we going to get home?” panic has seized American tourists in central Europe. The realization that if England’s navy is involved in a European war life on the Atlantic on even the finest liner de luxe will be fraught with danger sends a cold chill down the spine of many a “cure” guest and Continental automobilist who had hitherto felt no misgivings about returning to America at his leisure 9/10 are now busily figuring what steamers will safely carry them home. They know it is the business of warships not only to destroy an enemy’s warships, but also to capture or sink passenger ships. They are occupied, therefore, with trying to figure out on what route the peril is the least.

The crisis is proving a blessing in disguise to the Berlin hotels. They are experiencing the welcome novelty of entertaining Americans who stay a week or 10 days instead of the customary two or three days. The bottling up of Carlsbad, Marienbad, and other Austrian spas is mainly responsible for this state of affairs. Half the Americans now in Berlin were bound for Bohemian watering places, and are now remaining here until they can make up their minds regarding their plans.

The unprecedented spectacle of seeing the world’s greatest military nation girding itself for war provided the greatest conceivable excitement for American tourists in Berlin this week. One and all seemed disappointed, however, not to see the Kaiser or the Crown Prints galloping wildly up and down Unter den Linden, there being an apparently popular conception among Americans as to what Germany’s warlords ought to be doing at such an hour.

Among the interested onlookers at the historic scenes now taking place in the German capital this week were Martin Vogel, Assistant Treasurer of the United States, and his bride; Mr. and Mrs. Frederick L. Mandel, Mr. and Mrs. Maurice L. Rothschild, Mrs. J. W. Schwabach of Chicago, Mrs. George Quintard Horwitz, Miss Eleanor Newhall, Mrs. Andrew R. Dougherty, Miss Dorothy Cadwallader, and Mrs. Ralph C. Stewart, and Miss Margaret B. Wilson.

Lieut. Col. J. B. MacLean, the well-known Toronto publisher, and Mrs. MacLean are among the numerous Carlsbad refugees awaiting developments at the Adlon.

Other arrivals in Berlin are Mrs. W. M. Clarke and the Misses Dorothy and Lois Clarke of New York.

WEDNESDAY AUGUST 5, 1914

THE WAR SPIRIT

When, just before eight o’clock last night, the mobilisation proclamations calling up the Reserves and Special Reserves, and embodying the Territorial units, were published at the Birmingham Post Office, the railway stations, and other public places, there were remarkable scenes of animation. A large crowd assembled in front of the Post Office, and there were cheers when it was seen that the Government had decided to mobilise at once. The atmosphere was electric. Everybody talked of the impending war. Mostly there was the defiant spirit, and few thought of the morrow, when the dreadful accounts of battle will be rendered.

At Throp Street, where the Territorials are being mobilised, there were dense crowds to see the citizen soldiers come and go.

Correspondence

1st January 1914

To Abraham from Jacques. Written in French.

My dear Father

Before anything else, I wish you a good and happy 1914. l received your letter of Christmas and The Suffragette, Monday morning. I was very happy to learn that you spent the holidays so agreeably. We also had a good time. It is very cold, but the cold is pleasant, and we were able to go for a walk on Christmas Day. We went to have a look at the little huts and then went to visit S. On Sunday, we went to the Alhambra to see Fragson again. He died the evening before last, murdered by his father.

Rachel gave me an electric lamp as a present. She asks me to thank you for your present, which we received yesterday evening. It is very nice.

We have collected the money for the booklets 1. It came to about 200 francs. There was a loss of four francs per booklet, plus penalties, minors’ rights and membership. We shall send you the money if you wish.

I paid a quarter’s rent yesterday. Do not fret about where we are going to live. Our accommodation is assured now. To avoid our having to dip into the money for the booklets, please send 20 francs on Monday if you can, because we need it. Rachel has very little work at the moment.

I have read The Suffragette. The page, A Year’s Record is particularly interesting. I did not think the suffragettes had committed so many attacks this year. The damage they have caused amounts to at least 5,000,000 francs, an enormous figure. But they have good reason to behave as they have, because the best way to ensure that an idea will triumph is to take action. A single act of arson by the suffragettes is better than ten speeches, because an act touches the sentiments of the masses, while a speech affects only those who are able to hear and understand it. Also, I entirely approve of their course of action and their ideas, which are highly justifiable. A woman who works like a man and pays the same taxes, should have the same rights.

Those who oppose women’s rights in France cite two reasons for their opposition. The first is absurd: since women do not perform military service and thus do not defend their country, they cannot have the right to run the country. The second reason, which is more justifiable, is put forward by the Socialists: if women were to be granted the vote, their numbers would assure them of a majority, and they would elect a Parliament with a reactionary majority, which would impede the progress of the Socialist Party. This is a defensible and logical objection, but I cannot agree with it. If the Socialists are afraid of women’s ideas, how will they be able to make a revolution, if women oppose it? The Socialists’ reply is that the influence of women’s husbands will be quite powerful. Well, if that is really so, why are the Socialists afraid of women’s suffrage, since husbands will still exercise a sufficiently powerful influence on their wives to induce them to vote for Socialist ideas?

You see, I am a good feminist, and I think I could come to an agreement with your young friend.

I do not feel up to writing anymore, because it is holiday time. Enjoy yourself. Do not be sad. Wish everyone a Happy New Year for us.

Rachel wishes you good health and a good and happy year. She sends her love and wants very much to see you again. So do I.

Best wishes from all your friends here.

Your loving son who sends his love

Jacques

PS Send me Lisa’s address in America, because I do not have it here.

2nd January 1914

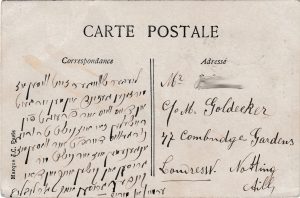

To Abraham from Herman and Miriam M. Written in Yiddish.

Beloved brother-in-law, be informed that we’re well and working. As to what you ask about Rachel, she isn’t sad, but you certainly should know that she isn’t feeling best pleased. We greet and kiss you, and the children greet you most affectionately. Herman and Miriam

Beloved brother-in-law, be informed that we’re well and working. As to what you ask about Rachel, she isn’t sad, but you certainly should know that she isn’t feeling best pleased. We greet and kiss you, and the children greet you most affectionately. Herman and Miriam

4th January 1914, London

To Rachel and Jacques from Abraham. Written in French.

My dear wife and son

I have received your New Year card and letter and am very happy to learn that you are well and are having a good time.

Now I can tell you that I have definitely decided to remain in London, and I hope to live as good a life here as I did in Paris. The only difficulty may be in connection with you, Jacques. Things may be awkward for you at the beginning, because of the language. Since you do not speak much English or Yiddish, you will be a little bored in our circle, but I hope that you will quickly get used to it. As for you, Rachel, I am almost certain that you will not regret coming to London, and you will be better off here than in Paris. I have relations and very kind friends here, and they will treat you as they treat me.

Write and tell me now whether you want to come to London. If not, I shall return to Paris. If you do want to come, you can begin selling the things that you will not be bringing with you to London, such as all the crockery, the bed and the table. Also, find out how much it will cost to send the chest of drawers, the mirror and the six chairs to London.

You, Jacques, can give in your notice to your boss. Tell him that your father is in London and wants to settle there permanently, and that is why you have to leave Paris. Ask him if he can help you to find a job in London. We’ll talk about everything else some other time.

I cannot send you any money this week, because I have not worked for almost a week, and I had to spend quite a lot for presents and other things because of the holiday. I do not think I shall be sending you any more money because, if I am going to remain in London, I shall need it to establish myself. Everything I earn I shall be earning for myself, and you will live on the money you have. Try to spend as little as possible. I would also like you to work out your month’s notice, because this will enable you to earn a little more money. Write and tell me how much more money you have altogether. I think that Mr. T. still owes you 65 francs, plus a further 35 francs that you lent him. Has it all been spent? Do not forget to write and tell me.

I have nothing more to write at the moment. I await your reply, so that I can start preparing to establish myself. My sister has still not been able to find a house for all of us, so she will stay on in her present accommodation, and I shall rent a place nearby that I have in mind, as soon as I receive a reply from you.

Looking forward to seeing you again, I send you much love and wish you to be of good heart. All my friends wish you a good and happy year and are sincerely looking forward to your arrival.

My best wishes for a Happy New Year to all my friends in Paris.

Your husband and father

Abraham

Mrs F.

1015 Grote Street The Bronx

New York

11th January 1914, London

To Rachel and Jacques from Abraham. Written in French.

My dear wife and son

Now I can write to you with greater certainty that I am going to remain in London, because I have already rented a place. I shall only start paying in three weeks’ time. They are in the process of redecorating it. There are two nice rooms looking onto a nice street, Cornwall Road, not far from my sister’s place. It is like rue de Montreuil near Place de la Nation, and I shall be paying six shillings a week. There is gas and water.

It is not because I am earning more that I want to stay. On the contrary, this is a very bad month in London. However, I must decide to do something so, since I hope to earn as much in London as I did in Paris and, perhaps, more, I will have to become accustomed to all kinds of work and change jobs.

I have decided to stay in London because I like the life here better than in Paris. You may well have difficulties at the beginning, because you will not be used to the life or the language, but that happens to everyone who changes countries.

Now you have to prepare to come to London, and you have to sell everything that has to be left behind in Paris, that is to say, the bed and the chairs. I want to buy a nice iron bed here, and chairs are not expensive in London. You can send everything else, even the crockery. Find out from a packer how much it will cost to send it all. I would like you to come in three or four weeks’ time, but you must send everything on before you come, so that I can establish myself and finish the mirror, if possible. Ask how much it will cost to send the chairs as well. Naturally, you will have to give your boss notice. If you do not stand to lose anything without doing so…

15th January 1914, Paris

To Abraham from Jacques. Written in French.

My dear Father

I have received your letter, and I am very pleased to learn that you are going to stay on in London. The living accommodation is not expensive. Is there a kitchen and gas for lighting? And is it the sort of place you like, with a garden and bow windows? Considering that it is in a big street, it is not at all expensive, and I think that Cornwall Road is such a big street.

Tell us the exact date you want us to come, so that I can give my boss notice and send you the mirror and the chest of drawers. The rest of the things we shall sell. Perhaps we shall keep the good crockery that is left. Do not worry about me and the language. I shall manage. As for the country, I shall have time to get used to it. At the beginning, I shall visit it, and later I shall work. I think that I shall take to English life.

Tell me what weather you are having. I do not see anything about it in the newspaper you sent me. Here, winter began on 21 December precisely. The 20th was mild; on the 21st, the temperature dropped to -2° C. Now the weather is nice and dry, with temperatures ranging from -5° to 0°, but it has only snowed heavily once. That was on Sunday. Now it has started to thaw, and we cannot even go for a walk. Everyone is complaining about it.

We are all very well and are having a pleasant time. I hope that you are the same. I have not yet been to see any packers but, as soon as I find out about prices, I shall let you know.

I have read the letter from Lisa. You see, you were wrong to be alarmed about her eyes. It was only a precautionary measure. You were right to tell her to sign herself “Lisa B.”. She ought not to forget her name. I was very pleased to hear that she is doing well at school. I imagine that she will not damage her eyes anymore, the way she used to before. I am writing to her. I shall send you a copy of the letter. She has changed a great deal since she was five years old, even since her last photograph. Her mother has changed very much as well, so much so, that I had difficulty in recognising her. She has grown younger and more refined. One would not have thought that it was the same person.

Do not be unhappy about our being apart. We shall all be together soon, and I hope we shall be happy. Give our love to everyone. All here wish you good luck.

I send you my love with all my heart.

Jacques B.

The same also from Rachel B.

18th January 1914, London

To Rachel and Jacques from Abraham. Written in French.

My dear wife and son

I received your letter yesterday, but I did not find the reply I was expecting. Try to give it to me in your next letter.

Find out from a packer, whom you can find in rue de Chevreul or from a removal’s office anywhere, how much it will cost to send the chest of drawers, the mirror, the chairs and the crockery. However, if you can find a buyer for the chairs for at least 3.50 francs each, you can sell them. If you are going to send the furniture, you must send it all at the same time – the books, the linens, the violin and all the knick-knacks and insure it all. You can leave the pictures, but I would like you to buy another two pictures like those we have with fruit, without frames, and two pictures of the sower and gleaner—they can be bought cheaply at the comer of avenue Ledrou Rolin – and some other landscapes.

I would also like you to buy some statuettes with baskets from the Italians, especially women or children, but do not get bronze-coloured ones, get terracotta-coloured ones. You can buy them cheaply. Put them in between pillows or wrap them in blankets, so that they do not break.

I would like you to come to London at the end of this month or a week later, depending on your arrangements and when you can be ready. As for me, I shall begin to establish myself next Sunday. I shall buy beds and tables, for which I shall borrow £2 or £3 from my brother-in-law. I want to have the rest of my furniture, so that I can set myself up completely, so that when you arrive, you can enter your home as if returning from a walk. Try not to spend money on clothes or linens, because they are much cheaper in London.

Now we come back to the same question your flat. What are you going to do now? I am afraid that the concierge will not let you take out the furniture unless you pay for the quarter. It might perhaps be more prudent to say that you want to have the chest of drawers repaired and the mirror finished. When you send the mirror, do not forget to put in all the pieces and the pieces of moulding. I shall need them. Bring the papers in the drawers as well, and all the notebooks. There is a little notebook with a black cover which is very old. It is from London, from when I worked on my own account, and I wrote down the workers’ pay in it. I want you to look after it, because I shall need it.

I have nothing more to write to you about at the moment. When I receive your answer, I shall write, I promise.

I send both of you much love and am waiting to see you again and wish you to be of good heart. All my family send their respects. They are also waiting impatiently to see you.

Regards to all my friends, and I ask them to give you a helping hand with your arrangements. Your impatient husband and father

Abraham B.

21st January 1914

To Abraham from Jacques. Written in French.

Mr B. at Davis G.’s house

47 Cambridge Gardens

Notting Hill. W.

London (England)

Give me the address of your new house. It’s Cornwall Rd. but I don’t know the number. We will come to London the last day of the month by the 8h25 train.

My dear father,

I have given the date of my holidays to my boss who was not happy about it because we have a lot of work at the moment. I will send you the day after tomorrow the cupboard and the mirror. It will cost 15 francs for packing and transportation to the train station. You will pay for the transportation in London. The chairs were sold 3.50 each to T. We will bring the books and the clothes/linen with us as hand luggage. It won’t be too heavy and we will add the tableware to it. I will be very careful about everything that you wrote me in your letter. Tell us right now whether we need to order 2 new mattresses to take with us or if we should rather not take any with us or if we should bring the old ones which are all dirty and damaged. Should we bring our two ripped blankets. Rachel is the one who wants to know all this. Reply right now. In my next letter, I will tell you about the books not to bring and about other things. We are in very good health—despite the brisk cold—5 degree this morning. We have a very cold winter this year. I will send two articles of the B.S. on the death of Francis de Pressensé 2 and of the General Piquart’ 3. We kiss you both. See you soon, write us a letter immediately.

We will say goodbye to Madame Bernard on Sunday.

23rd January 1914

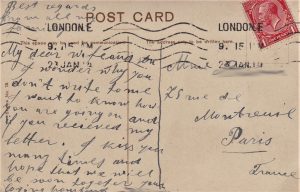

To Rachel and Jacques from Abraham. Postcard written in English.

Best regards from all my family

Best regards from all my family

My dear wife and son

I wonder why you don’t write to me I want to know how you are going on and if you received my letter. I kiss you many times and hope that we will be soon together your loving housband B.

Approx 24th January 1914

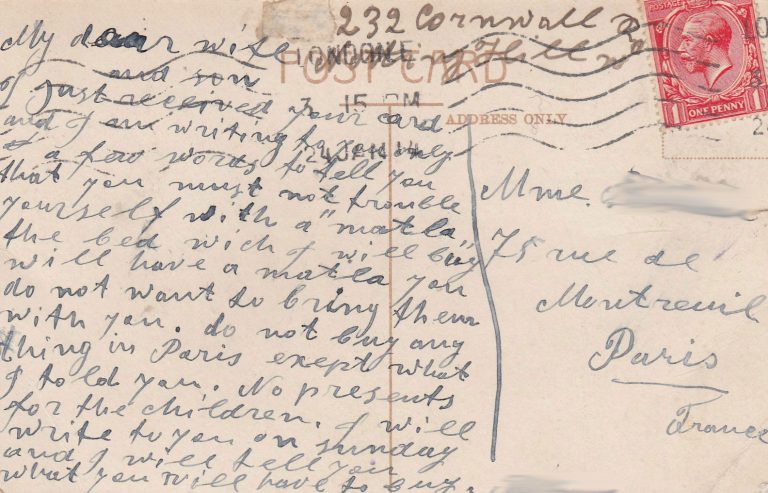

To Rachel and Jacques from Abraham. Postcard written in English.

My dear wife and son

My dear wife and son

I just received your card and I am writing to you only a few words to tell you that you must not trouble yourself with a “matla” the bed wich I will buy will have a matla you do not want to bring them with you. Do not buy any thing in Paris exept what I told you. No presents for the children. I will write to you on Sunday and I will tell you what you will have to buy. Abraham

25th January 1914

To Rachel and Jacques from Abraham. Written in French apart from the first line which is in English.

Dear wife and Jacque

I sent you a postcard yesterday, but I was not able to write much. I told you not to take mattresses. It is not necessary, because I have already bought a bed with a lovely mattress. I also wrote that you should not buy anything in Paris, because everything is available much more cheaply in London. The only things you could buy are statuettes and knick–knacks, but inexpensive ones. It does not matter whether they are plaster or chalk. Buy the statuette of the little girl reading a book, it is very pretty. In fact, you may as well buy two. I would prefer them to be yellow. And do not forget the pictures I mentioned in my last letter. Bring all the pictures we possess, all the crockery, all the books and all the literary sheets. Please send everything two or three days before you leave. Also buy some tie accessories if you can, and half a dozen ties, as well.

Now, Jacques, if your boss has not found anybody to replace you and wants you to stay on for another week, it is a good idea to do so, and you can then ask him for a reference.

That is all I can find to write to you about for the moment. When I have something else to write to you about, I shall do so. My sister is going to stay on in the same house, because she could not reach agreement with the owner of the new house she was interested in. We shall have a lovely place, and you will be very happy.

The weather is very cold in London, and it is the dead season in every trade. In my trade, the dead season will last for another month, and nobody will be earning very much, but it will pass…

Unfinished

29th January 1914, London

To Rachel and Jacques from Abraham. Written in English and French.

232 Cornwall Road,

Notting Hill, W.

Dear wife and son,

I cannot understand why you keep me waiting for a letter. Tell me how are you going in and whether you have sent already the things out. When you come don’t forget to bring a large de brou noir 4 and a demi livre d’acostic tout fait cher un marchand de couleur. Don’t buy anything, no wine no presents. It is not necessary.

With many kisses to my dear wife and son,

I remain, Your faithful husband and father, Abraham B.

Aw, this was a very nice post. In idea I want to put in writing like this additionally – taking time and actual effort to make an excellent article… but what can I say… I procrastinate alot and on no account appear to get something done.

Great write-up, I?¦m normal visitor of one?¦s website, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a lengthy time.

I’m not sure exactly why but this site is loading extremely slow for me. Is anyone else having this problem or is it a issue on my end? I’ll check back later on and see if the problem still exists.

Whats up very nice website!! Man .. Excellent .. Superb .. I’ll bookmark your site and take the feeds alsoKI’m happy to find a lot of useful information right here within the put up, we need develop extra strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Very efficiently written information. It will be helpful to everyone who usess it, including yours truly :). Keep up the good work – for sure i will check out more posts.